In hoc signo vinces...

I took the last week of September off as a much-needed vacation in the Adirondacks. We mostly went for the scenery, especially the beautiful fall leaves, but we also stopped at some historical sites. Two of those, including one I didn't expect at all, proved memorable.

The unexpected site was in Oswego, New York, a place I'd never been before. We followed signs for Fort Ontario to get to the Lake Ontario waterfront. Between the parking lot and a cemetery was a cross:

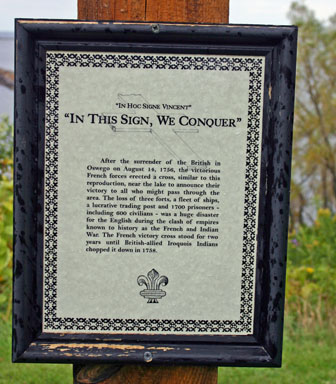

The sign on the cross provided a little more explanation for its presence:

Explanation for cross, reproducing a 1756 French victory cross.

(I think that "signe" should be "signo", and the "vincet" is typically "vinces", as in Constantine's classic In hoc signo vinces dreams, which led to Constantine's acceptance of Christianity and eventually its establishment in the declining Roman Empire.)

The original cross was raised in 1756, by the country of my father's ancestors, near the beginning of a war that also drove the Quakers out of government in Pennsylvania. In Pennsylvania, the French had built Fort Duquesne, which they would lose, like Oswego, in 1758. Pennsylvania shifted decisively from Penn's original vision during this war, culminating with the outrages of the Paxton Boys.

Quakers moved to the sidelines during this war, leaving the erection of victory crosses after a battle to others, arousing suspicion with their lack of support for the war, a suspicion that continued in later wars. While not all Quakers may have left the Pennsylvania Assembly over the war (as Margaret Hope Bacon contends in a note to Friends for 350 Years), this period saw their grip on political power shattered, never to return.

The other place we visited raises harder questions about religion and peace, and I'll write about it soon.

Comments

Obviously, you can't expect people who don't even know their latin grammar to come up with sound theology.

The outrages of the Paxton Boys had me wonder, though: What is the Quaker perspective on how to stop outrages like these? (Or say, criminal activity/selfjustice cases in general)?

Posted by: Presbyterian Girlfriend | October 12, 2006 10:53 AM

I don't really know Latin, but I think vinces vs. vincent mean "you conquer" (imperative) and "we conquer"... don't know about signe/signo though.

Posted by: Zach | October 14, 2006 9:52 AM

There are lots of possible answers to dealing with the Paxton Boys, few of them entirely thrilling.

First, I should point out that Quakers didn't object to the power of civil magistrates, to a degree not often seen today. To take one example, even at its most Quakerly, Pennsylvania did have the death penalty, though only for murder and treason, which was pretty constrained for its time.

It's clear that government had the means to pursue and punish the Paxton Boys, but it's far from clear that they had the will. Although the Wikipedia article cites their frustration with a Quaker government, by 1763 the government was more Anglican than Quaker, as many Quakers had departed government in 1756 at the start of the war.

In general it seems to me that the Quakers would have been able to prevent this only by preventing such people from going to the frontier in the first place, and given that these people weren't actually on the frontier - they were safely in Harrisburg and attacked peaceful Susquehannocks - it's hard to suggest what options there might have been for preventing it. The religious freedom that Penn promulgated wasn't (and couldn't be) limited to peace churches.

It's clear, in any case, that the government in 1763 had little idea what to do about this, and they were hardly hampered by pacifist ideals.

As a general answer for what Quakers might do today if they had command of the situation, I suspect sending out the police to arrest people would have to be the first option, with a long term goal of ensuring that people with views like the Paxton Boys aren't allowed to dominate their society. From their perspective, that would no doubt be a serious infringement on their freedom, but the old question of freedom's relationship to responsibility is hard to escape.

(I doubt that Quaker anarchists and those whose pacifism extends to law enforcement will like that answer.)

Posted by: Simon St.Laurent | October 17, 2006 2:43 PM

Well, the Quaker anarchist I'm most familiar with is beginning to mellow out a bit, towards what is sometimes termed "evolutionary" rather than "revolutionary" anarchism...

Though I still sympathize very much with something Gandhi said, to the effect of active nonviolence is better than violence, but violence (in the pursuit of just ends) is in turn better than simple cowardice.

Which leads to a two-tiered sort of ethics -- for the majority who seem to simply not be wired for spiritual things, law enforcement, intifada and defensive wars are just; but for those who are, unjust. Which still leaves me basically against Quakers participating in law enforcement.

Posted by: Zach | October 20, 2006 8:44 PM

There's a great book called The Crucible of War which treats what we call the French and Indian War as one of the first true World Wars, in which the British triumphed because they realized the advantages of mobilizing resources at that level.

I take from that analysis the insight that Friends realized they could not really hold their own at that level, that provinces such as Pennsylvania (and other, let us say, "autonomous zones") would be subsumed into the larger system of global imperialism. At which point they really did become more of a sect or denomination, one among many. And by the end of the American Revolution they were pretty much pushed to the margins -- in terms of the ambition of their original (e.g., Wm. Penn's) geo-political vision.

Posted by: Kirk Wattles | November 1, 2006 1:19 PM

I believe the declaration , " IN THIS SIGN WE CONQUER " is the correct translation for the Latin "in this sign we conquer ".

In hoc signo ( in this sign )

Vinces (Plural for "we conquer"

Posted by: Louis P Gagne | December 17, 2006 10:54 AM

This is my fraternities motto, and the latin we use is different. I do love how we are represented in near SUNY Oswego, we do not have a chapter there.

Posted by: Dave Hanzes | March 27, 2007 12:31 AM

yeah i like that

Posted by: samuel bagas | February 17, 2008 2:25 AM

“in hoc signo vinces.” The phrase means “in this sign you shall conquer” and was used by Constantine as a military motto in the early 4th Century. The phrase was also used by the original Knights Templar military order that was founded during the Crusades. The Freemasons began using Templar rituals and symbols in the late 1700s.

Posted by: peter rose | September 10, 2008 2:38 AM