Violence for the Golden Rule

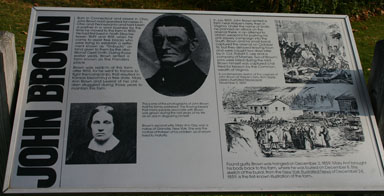

I mentioned earlier that I'd visited a second memorable historic site in my vacation last month. Again, it is memorable for being troubling: the home and farm, now a museum, of abolitionist John Brown.

John Brown's house, North Elba, NY.

John Brown moved to North Elba to help a group of black families who were trying to establish farms in a place that today supports very few farms. He wasn't home very often, as he was usually fighting his battles elsewhere, but his wife and daughters lived there and he and many of his family members are buried there.

Brown met his end in Virgina after he, his sons, and a small group of men seized the federal armory at Harpers Ferry, planning to arm slaves and free them. Despite a promising start - only a watchman guarded the armory - they were quickly at war with the surrounding countryside and arrested after various battles on the third day of their seizure. Brown was wounded, captured, and tried a month later. Found guilty on counts of murder, conspiracy, and treason (against Virginia), he was hung on December 2nd, 1859.

Brown's speech before his sentencing is widely quoted, but I find it strange in many ways. First, Brown denies that what he has done - while he did it - fits the description applied by the court in its judgment:

I have, may it please the court, a few words to say. In the first place, I deny everything but what I have all along admitted -- the design on my part to free the slaves. I intended certainly to have made a clean thing of that matter, as I did last winter when I went into Missouri and there took slaves without the snapping of a gun on either side, moved them through the country, and finally left them in Canada. I designed to have done the same thing again on a larger scale. That was all I intended. I never did intend murder, or treason, or the destruction of property, or to excite or incite slaves to rebellion, or to make insurrection.

That isn't exactly an unusual defense for a political prisoner, though it stands out against the background of Brown's prior work as a veteran soldier - an armed soldier - for abolition.

I have another objection; and that is, it is unjust that I should suffer such a penalty. Had I interfered in the manner which I admit, and which I admit has been fairly proved (for I admire the truthfulness and candor of the greater portion of the witnesses who have testified in this case)--had I so interfered in behalf of the rich, the powerful, the intelligent, the so-called great, or in behalf of any of their friends--either father, mother, brother, sister, wife, or children, or any of that class--and suffered and sacrificed what I have in this interference, it would have been all right; and every man in this court would have deemed it an act worthy of reward rather than punishment.

This part recognizes the frequent difference in treatment between those who fight for those in power and those who fight for the powerless, and may be the strongest part of Brown's speech.

Next Brown talks about his religious motivation for attempting to arm the slaves:

This court acknowledges, as I suppose, the validity of the law of God. I see a book kissed here which I suppose to be the Bible, or at least the New Testament. That teaches me that all things whatsoever I would that men should do to me, I should do even so to them. It teaches me, further, to "remember them that are in bonds, as bound with them." I endeavored to act up to that instruction. I say I am yet too young to understand that God is any respecter of persons. I believe that to have interfered as I have done--as I have always freely admitted I have done--in behalf of His despised poor was not wrong, but right. Now, if it is deemed necessary that I should forfeit my life for the furtherance of the ends of justice, and mingle my blood further with the blood of my children and with the blood of millions in this slave country whose rights are disregarded by wicked, cruel, and unjust enactments--I submit; so let it be done!

This paragraph brings us to a common reason for violence done in the Lord's name. The world is not as God says it should be, so it's up to people like John Brown to make it that way, martyring themselves in the process if needed. The guide at the house emphasized Brown's religious motivations, talking about his encounters at the age of 12 that conflicted severely with what he'd learned in church.

But do Brown's lofty ends justify the means? His reading of "do unto others" seems to imagine a future world, not his present one, and Brown seems clearly more interested in justice as an end than any sense of justice that might apply to the means he chose to arrive there. While I don't think Brown's strongly Calvinist background is a simple explanation for his choice of violent means, he certainly applied the Golden Rule very differently than Quakers would be likely to do in similar circumstances.

His vision of the future - while correctly predicting the Civil War to come - carries a similar perspective of redemption through violence, even greater violence than he had hoped to apply:

I, John Brown, am quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood. I had, as I now think, vainly flattered myself that without very much bloodshed it might be done.

Despite their different approaches, Quakers were very interested in Brown, and I'll have more on that in another entry soon.